We recently finished construction on this 22’x36′ timberfame carport in Southern Oregon.

We recently finished construction on this 22’x36′ timberfame carport in Southern Oregon.

When Ashland resident Barry Peckham decided to build his house, he had 4 main requirements.

When Ashland resident Barry Peckham decided to build his house, he had 4 main requirements.

1) He wanted it to be small. One of the easiest ways to cut down on building costs is to cut down on square footage, but small doesn’t have to mean uncomfortable. With about 672 sq. ft. of living space, one might think this 2 bedroom 1 bath house would feel cramped but Barry’s house is anything but.

2) He wanted it to be as natural as possible. According to Paula Baker-Laporte, architect and author of “A Healthy House”, there are over 88,000 chemicals used in the construction of today’s typical house. There is Material Safety Data for maybe 5000 of these chemicals and none of that data takes into consideration how those chemicals interact with each other. With the myriad of modern day health issues and the ever rising cost of healthcare, in this writers opinion (currently battling ALS), these are very valid concerns. Add to that the whole issue of global warming and the huge amount of greenhouse gases caused by the construction industry, it’s no wonder natural building is becoming more popular.

3) He wanted it to be as energy efficient as possible. With the ever rising cost of energy, it now makes more sense than ever to design and build using methods and technologies that can cut down the use of energy within the home.

4) He wanted a timberframe.

With these 4 main requirements, he came to see us at SwiftSure Timberwork and initially hired us to do the design work and ,once the timberframe was designed, to provide a price to supply and install the timberframe. Barry,  being a carpenter himself, had a pretty good idea of a floor plan and general design aesthetic.

being a carpenter himself, had a pretty good idea of a floor plan and general design aesthetic.

To meet his first requirement and to fit his floor plan into the small size that Barry wanted, SwiftSure used a Japanese style modular grid layout system. Since the overall dimensions of the house were set at 28’x32′, and the exterior walls are 12″ thick (more on that later) we ended up with a slightly unconventional 2’x2′-6″ grid. Despite being a non regular grid, this ended up working out quite well and created a unique feel to the layout of the house. For the timberframe design, in keeping with the Japanese style, all timber elements were situated on grid lines and intersections.

For the second requirement, Barry decided to use a light clay/straw exterior wall system. This system was pioneered by Robert Laporte and Econest (www.econesthomes.com) and is based of a very old European infill system. The exterior walls are 12″ of straw clay mixture that is packed into forms and once dry, they are plastered inside and out with natural clay or lime plaster. In our opinion, this creates the best, all natural wall possible. The combination of clay and straw create a wall that has both thermal mass and insulation. By mixing the clay and straw you also create a wall that will not mold or rot. The clay in the wall will absorb any moisture in the air and in doing so, will protect the straw. It will also protect the inhabitants of the home by absorbing any airborne toxins, as well as maintaining a humidity level throughout the year by absorbing moisture during the wetter seasons, and releasing moisture during the dryer seasons.

For the interior partition walls, Barry (and SwiftSure) devised a system of using only Pine paneling to eliminate the need for drywall. The timber frame was designed so that all interior walls were located within the frame.

The foundation was designed and built using Faswall (faswall.com) Insulated Wood Chip Form Blocks. This minimized the use of concrete as well as the need to use foam insulation.

Using the clay straw wall system also helped to make the house as energy efficient as possible. The combination of clay and straw create a perfect balance of insulation and thermal mass, which keeps the house warm in winter, and cool in summer. The small size also made a big impact on energy use, since we are often having to heat or cool the interior space in our homes, the size of that space will make a big difference on how much energy is required.

To drastically reduce to home’s reliance on fossil fuel for energy, Barry had Alternative Energy Systems (http://www.aesinc.us/) of Talent install a 10 panel photo-voltaic solar system on the house which produces upwards of 2410 kw/hr of electricity per year. Barry also had a 4’x6′ solar water heater installed which has provided nearly 100% of the house’s domestic hot water needs. Solar tubes were used in the kitchen and bathroom to help reduce electricity use and the house is heated via a radiant floor system which is one of the most efficient systems available.

Anyone familiar with the architectural styles of brothers Charles and Henry Greene will immediately recognize the softened, curving, sweeping lines that are a trademark of the houses designed and built by the brothers in the early part of the 20th century. Between the years of 1902 and 1911, the Greenes developed one of the most distinct styles of the Craftsman period. Heavily influenced by Asian aesthetics and design, these houses are masterpieces of craftsmanship. One of the defining features of the style is the extensive use of heavily shaped and intricately joined timber.

Over the years, SwiftSure has had the privilege to work on 2 fairly big projects that were done in the Greene and Greene style. The first of which was not only in the style, but was an original Greene and Greene design that had never been built. Originally designed in 1906 as the F.W. Hawks residence, this 4000 sq. ft. U shaped plan spent nearly 100 years in the archives until a local Rogue Valley builder decided to build it. When he first approached us about doing the project, we had never heard of Greene and Greene, and we had no idea of the intricacies involved in doing the timber work. The builder, Roger Whipple, an avid Greene and Greene fan and a true craftsman, hired us anyways and then showed us all he knew on properly creating the look and feel of Greene and Greene timber work.

The second project we worked on in the style was a massive 20,000+ sq. ft. project with over 100,000 bd. ft. of timber in Oregon, that sadly, was never properly completed. SwiftSure Timberworks did spend nearly 3 years on the project and in doing so we were able to learn much more about it and to figure out new methods for creating the proper look and also comply with modern building codes. Though the project was not fully completed, we did install nearly 30,000 bd/ft of timber which was part of 3 outbuildings, an extensive remodel, and 3 large Alaska Yellow Cedar Arbors.

Greene and Greene timberwork is all about subtle detailing. You could simply run a router down the edges and put a roundover on the timbers, but that doesn’t really give it that unique, special look. Every end gets softened and rounded, inside corners get chiseled a certain way, end profiles step up as they soar out to immense cantilevers. Everything is shaped by hand and is organic, therefore no two timbers are exactly identical. Curves are gentle and shallow, often compounding as they curve. Columns are often tapered over part of their length, or are built up of 3 layered timbers with hand forged wedged metal straps. All these details come together to form what we think is one of the most unique and beautiful styles of timber and wood construction that we’ve run across.

SwiftSure Timberworks’ most recent order was for a heavy timber truss, a ridge beam, and a set of timber hip rafters for a half-octagon ceiling over the living room of Ashen and Katelyn Carey’s new home in Ashland, Oregon.

Integrating heavy timber elements into projects that emphasize the use of natural building materials has been an important goal for SwiftSure Timberworks for many years. In 2011, we provided the timber framing for two Ashland homes that used a formed clay/straw mixture twelve inches thick for their exterior walls.

Katelyn Carey told me that when she and Ashen were thinking about the kind of home they wanted to build on their 24-acre property in the mountains southwest of Ashland, they decided early in the process that the design would be governed by certain key considerations, including:

• Energy efficiency

• Sustainability

• The use of high-quality, healthy building materials

They realized early on that the way the home site was located on the property would pose some constraints on how they approached the question of energy efficiency. For one thing, passive solar strategies such as south-facing windows could be ruled out: to the south, directly behind the home site, was a steep, heavily-forested hillside, and they knew that there were several weeks during the winter when the home site would see no sun at all during the day. On their home site, straw bale construction fit all three primary considerations: straw bales have very high insulation values (energy efficiency), and are a natural building material that contains no toxins and which are harvested every year (sustainable, healthy). Straw bales are also highly fire-resistant, which the Careys felt would be significant benefit on their heavily-forested property.

The Careys had read books like the Not So Big House by Sarah Susanka, and were sold on the idea that designing a house with a relatively small footprint would allow them the budgetary freedom to build a house where their own artistic bent could find expression. Knowing that they wanted an open living space, window seats, and a cozy kitchen, they designed the house themselves at first, and then took their sketches to Chris Keefe, the owner of Organicforms Design in Ashland (organicformsdesign.com) who was referred to them by Andrew Morrison, an Ashland-based builder who shares his expertise with straw bale construction through his website (www.strawbale.com) and through straw bale workshops he teaches all over North America. The straw bale walls for the Carey project will be installed in June, and will be the occasion of one of Andrew Morrison’s workshops.

A Tulikivi fireplace and heavy earthen floors will provide thermal mass to their home’s design, and the Careys estimate they’ll be able to heat their home with a half a cord of firewood each year. To learn how to build their own earthen floors, the Careys took a workshop on earthen floors from Robert and Paula Laporte, the Ashland-based natural building pioneers whose EcoNest building system (www.econesthomes.com) has won enthusiastic adherents all over the country. Claylin Floors of Portland, Oregon taught the workshop, and will be supplying the clay mixture the Careys plan to use for their earthen floors.

The Careys intend to do as much of the work themselves as possible, including the straw bale walls, the earthen floors, finishing, and the earthen plaster on the walls. They’ve hired professional subcontractors for other aspects of the work, including Herb Brower (Foundations), On Point Construction (Framing), SwiftSure Timberworks (Timber Truss), Alaska Masonry (Tulikivi), Applegate Plumbing (Rough Plumbing), Rogue Valley Electric (Rough Electrical), Childress Roofing (Roofing).

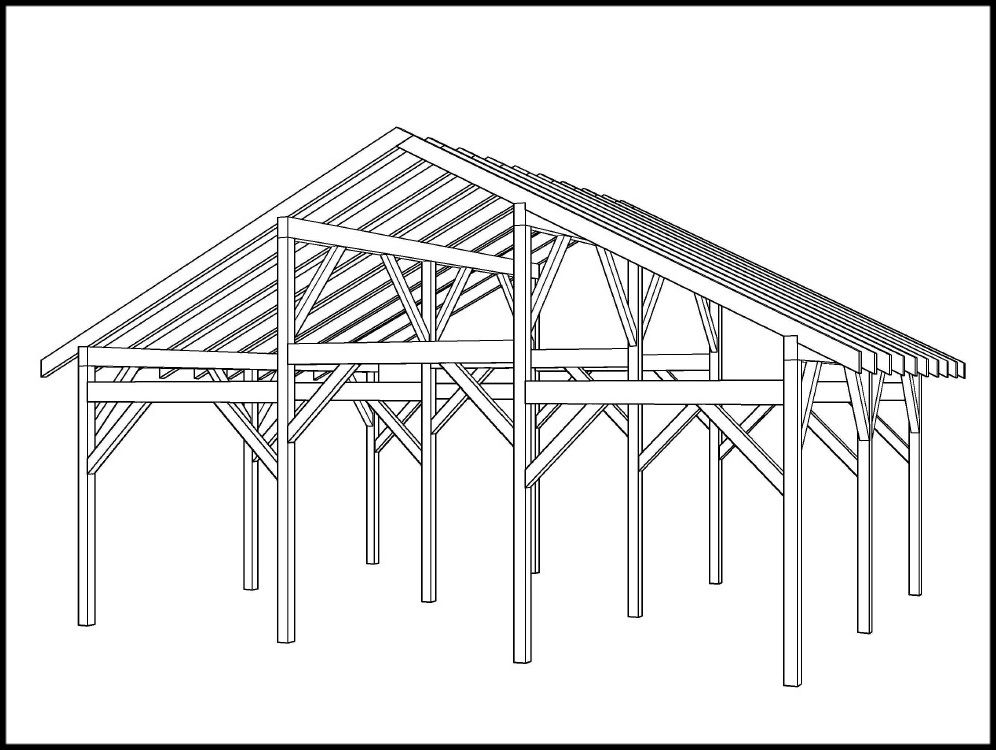

SwiftSure Timberworks LLC is proud to announce a new line of hand-crafted timber framed barn kits!

Timberframe barns have a long and rich history in America going back to the country’s earliest days. Some of the oldest existing buildings in the US are timber framed barns built by English and Dutch settlers on the east coast. Anyone who grew up around a timberframe barn has fond memories and a deep appreciation for the craftsmanship that created a structure that lasted centuries.

In an age of box stores and imported particle board furniture, our goal is to provide a locally, American made, hand-crafted product that is actually affordable, and will stand the test of time.

Our basic barn kit starts at $15,000 and includes these features,

24’x30′ Barn

4 10’x12′ stall locations (changeable to 12’x12′ as extra option)

10′ wide center aisle (changeable to 12′ as extra option)

All high quality timber with hand cut mortise and tenon joinery

10′ plate height at outer wall

6×6 Posts (12)

6×10 Beams (13)

4×6 Braces (32)

4×8 Rafters (20)

All hardwood pegs and GRK screws required for timber frame.

Detailed plans and installation manual.

To keep initial pricing as low as possible, price doesn’t include,

Installation (can be provided in Oregon for additional cost)

Delivery of Timberframe package to buyers site (can be included at additional cost)

Any required permits.

Any required engineering (can be included at additional cost)

Roofing, Siding, Doors etc.

Loft floor framing (can be included at additional cost)

Price if for cut and ready to install timber frame barn.

All sizing and dimensions can be customized and re-priced to fit individual needs.

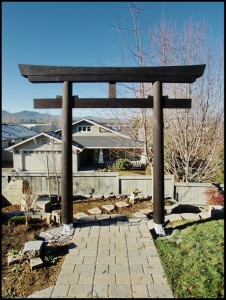

Last year, a client came to us with a photo of a Japanese engawa (roofed porch). The engawa and all the woodwork looked very old and very dark, as if decades or maybe centuries of sun and weather had worn the wood and the wood had turned a rich dark brown color.Perhaps it was helped with a stain, or maybe the carpenters had used this same technique, but it was quite beautiful never the less.

We had just finished the main timber frame for his house and we were just getting started cutting all the exterior timber work for his house. He told us that he wanted all the exterior timber to look like the wood in the photo. After looking at the photo for awhile, I remembered reading about an old technique of burning wood for a more weather resistant finish. After doing a bit of research, I ran across the term “Shou Sugi Ban”, which translates roughly to Burnt Cedar Siding. I told the client that we may be able to get the same look using this technique and that we would make up some samples for him.

After a bit of trial and error, we worked out a system that we think works well, and produces a gorgeous finish that you couldn’t get any other way.

The method we worked basically involves 4 steps. First we “torch” the wood, which leaves a layer of char or soot on the surface of the timber. Torching the wood achieves two main things. First, the early wood burns quicker than the harder late wood so that when scrubbed off, more early wood has been removed so you end up with a beautiful “weathered” texture.

The method we worked basically involves 4 steps. First we “torch” the wood, which leaves a layer of char or soot on the surface of the timber. Torching the wood achieves two main things. First, the early wood burns quicker than the harder late wood so that when scrubbed off, more early wood has been removed so you end up with a beautiful “weathered” texture.  Secondly, the fire and heat don’t penetrate into the wood very far so that beneath the soot, a layer is created where the wood has been heated to such a degree, but hasn’t actually burnt, that it turns a rich chocolate brown color. The late wood burns at a higher temperature than the early wood so it ends up being darker. This creates a look that is opposite to what you would get by using a stain.

Secondly, the fire and heat don’t penetrate into the wood very far so that beneath the soot, a layer is created where the wood has been heated to such a degree, but hasn’t actually burnt, that it turns a rich chocolate brown color. The late wood burns at a higher temperature than the early wood so it ends up being darker. This creates a look that is opposite to what you would get by using a stain.

After torching, we scrub the soot off using water and a stiff bristle floor scrub brush. We tried a wire brush but found it was too course and would scratch the colored layer just below the soot. Once most of the soot has been scrubbed and rinsed off, we move the timber indoors and do a final cleaning using wet rags to buff and polish out more soot. Finally we oil the timbers using a natural clear finishing oil.

Shou Sugi Ban is a gorgeous, unique finish that gives wood the appearance of being centuries old and a color that we believe no stain can match.

Welcome to our new website. After nearly 10 years of great service, we have given our website a complete overhaul. While there were many things we loved about our old website, the march of time is never ending, and technology is ever changing, and so our website had become a little out of date.

Our new website has a host of new and better features. We have better galleries with lots of new and better photos, we will have more information about us as well as more info on timberframing and timberframing techniques, we will have more info on all the great services we provide, and we will have a blog/newsfeed where you can keep up to date on all the great things we are doing.

Our new site was developed by local web developer Jesse Hodges. We are very thankful for all the great work he has done to make our new site better than we had hoped. You can find out more, as well as contact Jesse at http://jessehodg.es/

Please take some time and have a look around.

Thanks,

Tim, Shona, and Colton